In the 1950s, my sister and I grew up in a world that felt both safe and unyielding—a world of Formica kitchen tables, the clink of milk bottles on the doorstep at dawn, and the ever-present hum of the Philco radio, its warm glow filling the kitchen with Perry Como and the news of the day. Our home was a patchwork of pastel wallpaper, the scent of lemon polish, and the gentle clatter of breakfast dishes. But beneath the gentle rhythms of suburban life, discipline was a constant, as much a part of our days as the sun rising over the maple trees.

My mother was the axis around which our world spun. She was a woman of deep, unwavering faith, her Bible always within reach, a simple cross at her neck, and her hair pulled back in a no-nonsense bun. She dressed plainly, favoring modest floral shirtwaist dresses and sturdy shoes, her manner as direct as her faith. She was not a woman given to frivolity or sentimentality, but there was a quiet strength in her presence—a certainty that radiated from her, as if she carried the weight of generations of mothers before her. Her faith was woven into every detail of our lives, from the grace she said before every meal to the hymns she hummed as she ironed our clothes.

Discipline, for Mother, was not just a duty—it was a sacred responsibility, a way to shape our character and keep us on the right path. Like most Christian parents of her era, she believed in the principle of “spare the rod, spoil the child.” But for her, it was more than a proverb; it was a commandment, a calling. She saw each spanking or thrashing as her godly duty, acting with a sense of righteousness and certainty that she was fulfilling her Christian responsibilities as a parent. Her actions were deliberate, never cruel but always firm, and she believed that to do less would be to fail us—and to fail God.

I remember the rituals of discipline as clearly as the rituals of Sunday morning. If we misbehaved, Mother gave us one warning—her voice calm but steely, her eyes sharp behind her glasses. After that, the consequences were swift and sure. Sometimes it was the paddle, sometimes a switch from the willow tree out back, but always with the same unwavering conviction. Afterward, we’d stand in the corner, facing the wall for what felt like an eternity—usually twenty or thirty minutes, though it seemed much longer to a child’s mind. Mother always said the punishment should fit the crime, just like the advice in her Ladies’ Home Journal, but she also reminded us that “to spare the rod is to spoil the child,” quoting Proverbs with unwavering conviction. In her eyes, discipline was a necessary expression of love, a way to guide us toward goodness, just as her faith and the times demanded.

There were moments, though, when I glimpsed something softer beneath her stern exterior. I remember once, after a particularly hard day, finding her in the kitchen, her hands trembling as she kneaded bread dough, her eyes red-rimmed. She never spoke of her own struggles, but I sensed the burden she carried—the weight of raising two daughters alone after my father’s accident, the endless work, the constant worry. Sometimes, late at night, I would hear her praying softly in her room, her voice barely more than a whisper, asking for strength and guidance.

One afternoon, my sister Julie took and hid one of my favorite comic books—an issue of Little Lulu I’d saved my allowance for. It was a small thing, but to me, it felt like a betrayal. When she left the house for a few minutes, I went searching, not realizing she’d stashed it in the den, a room where I’d been told never to leave my things.

So I crept into her room, searching under her chenille bedspread, rifling through her dresser drawers. The room was filled with the scent of talcum powder and the faint sweetness of her bubblegum stash. By the time Julie returned, her cotton petticoats and plaid skirts were strewn everywhere, and her Shirley Temple dolls were in a heap on the linoleum floor. Of course, she ran straight to Mother, her voice high and indignant, her cheeks flushed with outrage.

Mother came back to find Julie’s room in complete disarray. With her lips pressed tight and her eyes sharp behind her glasses, she said I’d get a good tanning—and that wasn’t all—for embarrassing Julie in front of her playmate from next door. She promised I’d be just as embarrassed. There was no arguing with her; her word was law, and she enforced it with the same certainty she brought to Sunday service. I remember the way her voice seemed to fill the room, calm and unyielding, as if she were reciting scripture.

Mother told me to go out to the backyard and cut her a switch, just as I was, in my knee socks and Mary Janes. My cheeks burned redder than a cherry Popsicle as she nudged me out the screen door. I hoped the neighbors wouldn’t see as I made my way to the willow tree, the summer air thick with the scent of cut grass and distant barbecue smoke. The walk to the tree always felt like a journey of shame, each step heavy with dread and regret.

I remember the feel of the willow branch in my hand, its green bark cool and slick, the leaves trembling in the breeze. I would always try to pick the thinnest, most flexible switch, hoping it would hurt less, but Mother always inspected it, sometimes sending me back for another if she thought it too flimsy. There was a strange intimacy in that ritual—a silent understanding that this was as much about obedience as punishment.

When I returned, Mother pulled a wooden chair—one of the sturdy maple ones from the dinette set—into the center of the living room and told me to bend over it. The room felt impossibly still, sunlight slanting through the lace curtains, dust motes swirling in the air above the braided rug. My heart pounded as I gripped the worn cushion, the nubby fabric rough beneath my fingers. The air was heavy with the scent of furniture polish and the faint, green smell of the willow switch. I could hear the ticking of the wall clock and my own quick breaths, and the creak of the floorboards as Mother stepped behind me. I knew Julie and her friend were peeking from the hallway, their whispers barely louder than the radio playing Perry Como in the kitchen.

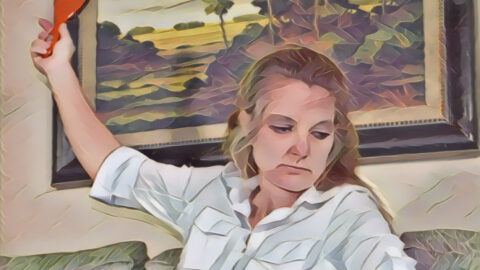

(short pause) When Mother raised the switch, she did so with a sense of purpose, never hesitating or holding back. Each stroke was delivered with the full force of her conviction, as if she were channeling the weight of her faith and the expectations of her generation. The switch whistled through the air—a sharp, menacing sound that cut through the hush. Then—crack!—a searing, stinging pain exploded across the backs of my legs. I gasped, my eyes watering instantly.