(gap: 2s) I was born into a world in transition—a world where the echoes of old discipline still lingered in the air, even as the laws began to change. Corporal punishment had been banned in UK state schools by the time I arrived, but in private schools, especially those with religious ties, the old ways clung on stubbornly. My family, deeply rooted in faith, were devout Christians, and our lives revolved around the rhythms of church and community. I attended a private school run by our church, a place where the boundaries between faith, family, and discipline blurred until they were almost indistinguishable. The school itself became embroiled in a lawsuit in the late 90s, alongside dozens of others, arguing that banning corporal punishment was an affront to religious freedom. For us, it was simply the way things were—a tradition handed down, justified by scripture and custom, and woven into the fabric of daily life.

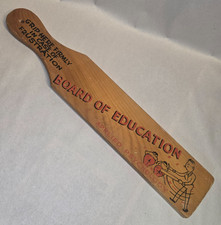

The implements of discipline at school were legendary, spoken of in hushed tones among the children. There was a paddle for boys—smooth, polished wood, heavy in the hand, its surface gleaming with the oil of countless anxious palms. For girls, a thick, folded leather strap, dark and supple, with a faint scent of polish and fear. Both were kept in a locked drawer in the headteacher’s office, a place that seemed to exist outside of time, where the air was always a little colder and the silence pressed in on you from all sides. The mere mention of those implements was enough to send a shiver down your spine, and we would speculate endlessly about who had received them last, and how many strokes they’d endured.

To be fair, the school did not reach for the paddle or strap lightly. There were warnings, detentions, and stern lectures first. But the threat was always there, a shadow at the edge of every misstep. On average, there were at least two paddlings or strappings a week—more often boys than girls, though no one was truly safe. The ritual was always the same: the summons to the office, your name called out in front of the class, the slow, heavy walk down the corridor. You would sit outside the headteacher’s door, heart pounding, the muffled sounds of lessons continuing behind closed doors. The silence was thick, broken only by the sound of your own breathing, and the knowledge that soon, you would be called in to face judgment.

I was still at that school when the law finally caught up, and corporal punishment was banned in private establishments as well. But the change was more symbolic than real. The pain simply shifted from the hands of teachers to the hands of parents. Instead of being punished at school, you were given a red slip—a piece of paper, bright and ominous, with your name and the prescribed punishment written on it. That slip felt heavier than any paddle, its crimson edge a warning, its message a sentence. I remember the first time I held one, my fingers trembling, the paper seeming to burn against my skin. The walk home with that slip in your pocket was a torment—each step a countdown, the weight of dread growing with every footfall. You could feel the eyes of the community on you, the knowledge that everyone knew everyone, and secrets were impossible to keep.

At home, the ritual continued, but it was more intimate, more personal. My father had passed away when I was still young, leaving my mother to shoulder the burden of both parents. She was a woman of deep faith and fierce determination, but the strain of raising two boys alone sometimes showed in ways that frightened me. Her moods could shift like the weather—one moment gentle and nurturing, the next sharp and unpredictable. The loss of my father hung over our home like a shadow, and my mother, trying to fill the void, sometimes seemed to be fighting battles none of us could see. When the red slip system began, it was my mother who became the enforcer, her authority absolute, her love complicated by the weight of responsibility and grief.

I remember the first time I was paddled at school. The fear was almost worse than the pain. You would be called in, asked to confess your ‘sin’—a word that carried so much more weight in a religious school. Then you’d bend over the back of a chair, the fabric of your trousers stretched tight, and wait for the blows. Three to five hard smacks, each one ringing out in the silent office, the sting sharp and immediate. Afterwards, you would pray with the headteacher, asking for forgiveness and strength. All punishments were reported to parents, and some children would face a second round at home. My mother, for all her strictness, never punished me again if I’d already been spanked at school, though she did not hesitate to discipline me and my brother for other infractions. The pain was real, but it was the anticipation—the waiting, the not knowing—that left the deepest mark.

When the red slip system took over, everything changed. The punishments at home were far harsher than anything I’d experienced at school. The living room would become a stage for a private drama, the curtains drawn tight, the air thick with tension. My mother would call me in, her voice steady but cold, and I would know what was coming. Sometimes she would use the same belt that hung in the hallway, a silent threat in plain sight, its presence a constant reminder of what could happen if I stepped out of line. She would tell me to bend over her knee or the arm of the settee, and then the punishment would begin—ten, sometimes twenty hard smacks, each one landing with a crack that seemed to echo through the house. The pain was immediate, a hot, stinging fire that made my eyes water and my breath catch. I tried to be brave, to hold back the tears, but sometimes the pain and shame were too much. Afterwards, there would be a strange, heavy silence—a mix of relief, humiliation, and a lingering ache that seemed to settle deep in my bones.

I often wonder if the red slip system still exists, if other children are still carrying that same burden home, their hearts pounding with fear and shame. I hope not. My own story took a different turn after my mother remarried—a man I never truly connected with, whose presence only deepened the sense of isolation I felt. In time, I turned away from Christianity, seeking solace and meaning in other paths, eventually finding myself drawn to witchcraft and the quiet power of nature. My relationship with my family grew distant, the ties of blood and faith stretched thin by years of misunderstanding and pain. Yet the memories remain, vivid and unyielding: the rituals of discipline, the fear and anticipation, the complicated love that bound us together in that small, suburban house. My mother did her best—sometimes faltering, sometimes fierce—trying to fill the space my father left behind. And I, in turn, have spent a lifetime trying to understand the legacy of those years, the ways they shaped me, and the ways I have learned, slowly and painfully, to forgive.