(gap: 1s) Ours was a typical hard-working East End family, living on a rough council estate in Bethnal Green in the late 1960s. The air always seemed tinged with coal smoke and the distant tang of vinegar from the chip shop. Dad worked long hours at the docks, his hands always rough and smelling faintly of engine oil, while Mum kept the flat running—her days a blur of laundry, shopping at the Co-op, and making sure we never went without, even if money was always tight.

(short pause) The estate was a world of its own. Rows of soot-stained brick terraces, washing lines strung between lampposts, and the constant clatter of kids in patched jumpers and worn plimsolls racing battered Raleigh bikes. Mums gossiped by prams and Ford Anglias, their voices carrying over the sound of a rag-and-bone man’s bell and the distant rumble of the number 8 bus.

(pause) I remember the smells most of all—boiled cabbage, damp concrete, and the sharp tang of carbolic soap. Our flat was cramped but always warm, thanks to the two-bar electric fire and the thick crocheted blankets Mum made herself. The sitting room was the heart of it all, with faded floral curtains, a battered Beatles LP sleeve on the coffee table, and the black-and-white telly flickering with “Blue Peter” or the football results.

(short pause) I’ve got an older brother and a younger sister, and out of the three of us, I copped the most hidings by a fair stretch. On the ‘sore bums table’ my sister came next, while our big brother got off the lightest. That was just the way things went in families like ours—discipline was part of life, and nobody thought much of it.

(pause) My brother and I got a clip round the ear or a smack from both Mum and Dad, but my sister only ever got it from Mum. I remember once, Mum went up north for a cousin’s wedding, and my sister got herself in trouble on the Friday afternoon. Mum wasn’t due back till Monday, and by Sunday my sister was beside herself with worry, begging Dad to just get it over with because she couldn’t stand the waiting.

(short pause) There was a kind of ritual to it all. Mum’s hairbrush—heavy, wooden, with a few bristles missing—sat on the Formica sideboard, next to a postcard from Southend Pier and a chipped mug full of loose change. My sister got Mum’s hairbrush across her backside at least once a month, and honestly, it was worse than Dad’s hand or slipper by a long shot. She’d howl and carry on as the hairbrush did its work, but Mum never let up. That was the East End way—tough love, but always with a roof over your head and food on the table.

(pause) Sometimes, after a hiding, my sister would lie face down on her bed, sobbing into her pillow, the faded wallpaper and a peeling Rolling Stones poster her only company. I’d sit on the stairs, listening to the muffled sounds, feeling a strange mix of relief and guilt that it wasn’t me this time.

(short pause) The most memorable—or maybe the worst—hiding I saw my sister get was a bit later on. By then, she hadn’t been spanked in months, and we were all getting a bit older, but the estate was still the same—rough around the edges, but full of hard-working families just trying to get by.

(pause) She’d developed a proper attitude—nothing terrible, just being a right madam, rolling her eyes and giving lip, that sort of thing. It was the kind of cheek you’d see from kids all over the estate, but Mum had her limits.

(short pause) One day, Mum finally lost her patience. “Right!” she said, “let’s see if a good hiding sorts you out.” My sister actually laughed and said, “I’m too old for that now!”—as if growing up on a council estate made you immune to a mum’s temper.

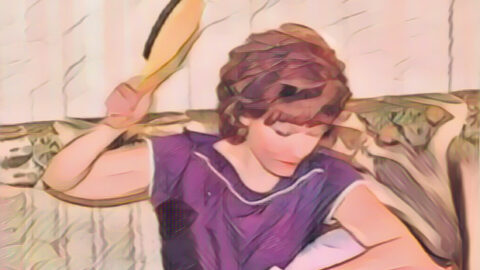

(pause) Mum clearly disagreed. She wrestled my sister over her lap right there in the kitchen, and started in with her hand. I stood there awkwardly, half watching, half wishing I was somewhere else, until Mum turned to me and, over my sister’s yells, said, “Go on, love, fetch my hairbrush from the sideboard, will you?”

(short pause) I did as I was told, because in our family, you didn’t argue with Mum—especially not in front of the neighbours. I remember the feel of the hairbrush in my hand, heavy and cold, and the way the sunlight struggled through the net curtains, making dust motes dance in the air.

(pause) When I came back, my sister was shouting and telling Mum to stop. But once the hairbrush got going, the shouting turned to pleading and begging. The sound of it—sharp, rhythmic, echoing off the kitchen tiles—still makes me wince when I think about it.

(short pause) In the end, she collapsed, sobbing and twitching with every whack. Mum gave her a real stinger across the backs of her legs and said, “Any more cheek, young lady, and I’ll let your Dad take the slipper to you.”

(pause) Looking back, I doubt Mum would’ve actually let Dad do it—but the threat was enough, and my sister only got one or two more hidings for the rest of her childhood.

(short pause) Life on the estate was hard, but there was always a sense of togetherness. We’d crowd into the sitting room on Sunday evenings, sharing a pot of Typhoo tea and a plate of Penguin biscuits, the telly flickering in the corner. Sometimes, if we were lucky, Dad would bring home a bag of chips wrapped in newspaper, and we’d eat them straight from the paper, fingers greasy and faces glowing in the lamplight.

(pause) I remember the jumble sales at the church hall, the excitement of finding a nearly-new jumper or a battered toy, and the way the mums would swap gossip over cups of stewed tea. There were fights and fallings-out, but also laughter, birthday parties with jelly and blancmange, and the endless games of football in the yard until the streetlights flickered on.

(short pause) Evenings would settle over Bethnal Green with a kind of weary peace. The estate would quieten, the last shouts of children fading as mums called them in for tea. The glow of windows, the smell of toast and baked beans, the distant strains of Dusty Springfield from a neighbour’s radio—all of it is stitched into my memory.

(pause) That was life for a working-class family on a tough East End estate—hard, sometimes harsh, but always together. And even now, when I catch the scent of carbolic soap or hear the distant ring of a bicycle bell, I’m right back there—home.