Once upon a time, in a cheerful row of red-brick houses, there lived a little boy named Peter with his mother and father. Their home, number 17, stood proudly behind a white gate, its garden a patchwork of dandelions and roses, tended with loving care. The air on their estate was always fresh and lively, filled with the scent of cut grass, new paint, and the gentle curl of coal smoke from the chimneys. On Sundays, the world seemed to slow and brighten, as children in short trousers and woolly jumpers whizzed by on Raleigh bicycles, their laughter ringing like bells across the communal green. Mums in flowery dresses gathered by the privet hedges, their voices a gentle hum of stories and smiles, while fathers, with sleeves rolled up, polished their Morris Minors or leaned on garden gates, sharing tales of days gone by.

Inside Peter’s house, the living room glowed with warmth and order. Net curtains softened the sunlight, floral cushions sat plump and inviting, and the electric fire hummed a comforting tune. On the coffee table, a Lonnie Donegan record sleeve hinted at music and merriment, though it was rarely played when Mother was near. The black-and-white telly flickered with “The Grove Family,” and atop the sideboard, a crocheted doily rested—a badge of Mother’s pride in her tidy home.

Peter’s father was a gentle giant, his hands rough from honest work at the factory, his eyes kind but touched with a faraway sadness. He was a man of few words, believing in the quiet dignity of doing one’s duty. Each Sunday, he polished his shoes until they shone, then ruffled Peter’s hair with a rare, twinkling smile before heading to the allotment or the pub for a friendly pint. He was steady as a rock, a comforting presence in a world that sometimes felt big and uncertain.

Mother, on the other hand, was a whirlwind of energy and spirit. Her roots stretched back to a gypsy caravan, and though she now lived in a sturdy council house, a wild spark still danced in her eyes. She moved briskly through the rooms, her temper quick but her love fierce and true. The neighbours sometimes whispered about her fiery ways, but Peter knew there was a strength in her—a will to keep her family safe and sound. Her hands could be gentle as she pinned a nappy or brushed Peter’s hair, but when her temper flared, it was like a summer storm—sudden and strong, but soon passing.

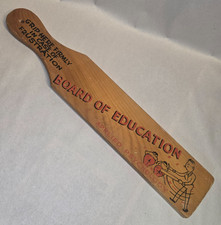

One evening, as the living room still smelled of new wallpaper and coal dust, a hush fell over the house. Peter had begun to wet the bed—a secret he tried to keep, but which Mother soon discovered. Her eyes flashed, and her voice grew quiet and serious. “He needs a proper lesson,” she said to Father, her words hanging in the air. With a heavy heart, Father fetched the leather belt from the sideboard, its brass buckle shining in the lamplight. He looked at Peter with sad, tired eyes, and Peter knew this was not a task Father wished for. Bent over the wooden stool, Peter squeezed his eyes shut, his heart thumping like a drum.

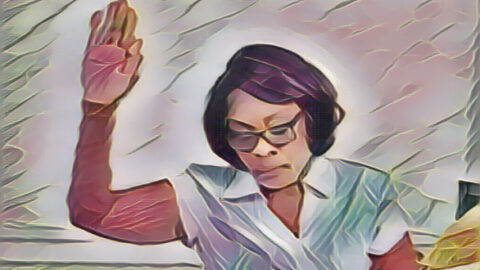

The first stroke of the belt landed with a soft thud, the leather stinging through Peter’s thin shorts. The room was quiet, save for the hum of the electric fire and the distant laughter of children outside. Father’s hand trembled as he delivered each of the six strokes, gentle rather than harsh, as if hoping Peter would hardly feel them. Father was always fair, never cruel, and his discipline was measured and mild. Yet, it was Mother’s look of disappointment that stung most of all—her arms folded, her jaw set, her eyes as hard as flint. There was no softness in her then, only a fierce determination that Peter would learn his lesson.

Suddenly, Mother’s patience snapped. Her eyes flashed as she took the belt from Father’s hands. “Hold him steady,” she said, her voice as cold as the winter wind. Father’s hands held Peter’s shoulders, careful but firm. The belt whistled through the air and landed with a sharp crack, making Peter gasp. Again and again, the leather struck, each time a little harder, the sound echoing like a judge’s gavel. Mother’s temper was quick and fierce, but her love was just as strong. Tears pricked Peter’s eyes, but he bit his lip, determined not to cry. Mother’s face was set, her jaw tight, her gypsy pride shining through every stroke.

When it was over, Peter’s skin was hot and sore, red marks rising where the belt had landed. Mother’s anger faded, replaced by brisk care. She led Peter to the bathroom, where steam curled from a freshly drawn bath. The water stung, but Mother scrubbed him clean, her hands gentle once more. Wrapped in a towel, Peter was carried to the lounge and laid on the settee. Mother pinned a thick cloth nappy around him, her hands soft but her eyes still stern. The safety pins clicked shut, and Peter’s cheeks burned with shame. He remembered the scratchy feel of the nappy, the rustle of the plastic sheet, and the way Mother’s hands lingered, as if she wished to comfort him but didn’t quite know how.

For many nights, bedtime became a time of worry and dread. Each evening, Mother would tiptoe into Peter’s room, her footsteps soft on the linoleum. If she found him wet, her face would harden, and her temper would flare. Out came the belt, followed by a brisk cold bath that left Peter shivering. Father, away for work more often now, left all discipline to Mother. Peter would lie in bed, listening to the distant clink of milk bottles and the gentle rumble of the milk float, wishing he could disappear into the night.

As Peter grew, the punishments changed. No longer small enough to fit over Mother’s knee, he would lie face down on the bed, feet on the floor, his bottom raised. The room would be silent, save for the swish and crack of the belt, and the scent of soap and liniment in the air. Mother’s face was focused, her arm strong—a strength born of her caravan days and quick temper. Each blow was sharp, but beneath the pain was a strange, confusing feeling—a mix of fear, shame, and something Peter could not name. Sometimes, after the punishment, Mother would sit beside him in silence, her hand resting on his back, her breathing slow and steady. In those moments, Peter sensed a sadness in her, a longing for something lost.

The estate itself seemed to watch over Peter’s family, its quiet roads and tidy gardens keeping their secrets. At dusk, porch lights glowed, casting long shadows, and the sound of radios drifted through open windows. Peter would watch the other children from his bedroom window, their laughter echoing across the green, and wonder if their homes were as full of secrets and storms as his own.

The pain was real, and the lessons unforgettable. Yet, as the years passed, Peter found himself both dreading and longing for those moments. (long pause) Looking back, he saw that those Sunday lessons shaped him, for better or worse. In those days, a boy learned right from wrong not just from words, but from the sting of the belt and the steady hand of a father who had seen war, and a mother whose wild spirit could never quite be tamed. Though times have changed, the memory of those lessons lingers, as bright and clear as the day the estate was new. The estate, his parents, and those Sunday lessons are woven into the tapestry of Peter’s childhood—each memory a thread, bright and unforgettable, in the story of a little boy growing up in a world of red brick and roses.