(gap: 2s) Once, in the gentle days of my childhood, I was the only child in a modest home nestled in the heart of old Kolkata. The air was always tinged with the comforting scent of coal smoke, and the distant clang of trams was a lullaby to our daily lives. My school, run by kindly but firm Christian missionaries, was a place where order and discipline reigned supreme. The rules were as solid as the stone steps leading to the chapel, and every child knew that a sharp word or a swift smack was never far away if one strayed from the path of good behaviour.

My dear mother, like so many wise mothers of her time, believed that a child’s character was shaped by a firm hand and a loving heart. She watched over me with the keen eyes of a hawk, always ready to correct a wayward glance or a mischievous thought. A single look from her—eyes wide, nostrils flared, lips pressed into a thin line—was often all it took to remind me of my duty. She rarely needed to raise her voice, and never her hand, for her presence alone was enough to keep me on the straight and narrow.

(short pause) But the world was changing, as it always does. One day, the government declared that corporal punishment was to be banished from schools. The news swept through the classrooms like a fresh breeze, and we children rejoiced, our hearts fluttering with the hope of newfound freedom. Yet, the teachers wore anxious faces, and at home, my mother’s lips grew even thinner. She, like many parents of her generation, feared that without the guiding hand of discipline, children would lose their way and the world would fall into disorder.

That year, I was in Year 7, and the annual examinations loomed like great storm clouds on the horizon. In years past, I had always brought home marks that made my parents proud. But this time, my results were disappointing—no subject above ninety percent, and my class rank slipped by five places. My mother was silent all day, her disappointment as heavy as a rain-soaked coat. When my father returned from work, she quietly withdrew to her room, and the house was filled with a hush so deep that even the clatter of cutlery at dinner seemed muffled.

The next morning, as the golden sunlight crept through the curtains, my mother emerged, her composure restored. “You shall not be idle,” she announced, her voice gentle but resolute. “Until school resumes, I shall be your tutor. We will have lessons in the morning, afternoon, and evening. Your father and I have agreed, and there will be other measures as well.” There was no room for argument, for her word was law in our home.

That afternoon, she set me to my studies while she went out on an errand. When she returned, she carried a long, thin parcel wrapped in brown paper. She disappeared into her room with it, and I felt a shiver of foreboding run down my spine.

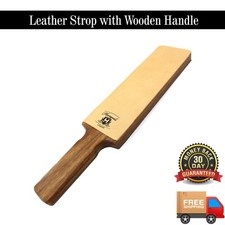

Evening came, and I was summoned to my room for my lesson. I sat at my desk, my books open, my heart thumping like a drum. I heard her footsteps in the corridor, steady and purposeful. She entered, the mysterious parcel in her hands. With careful, deliberate movements, she unwrapped it before me. Inside was a rattan cane, about a metre long, its surface gleaming with wax, the handle wrapped in black cord. It was just like the canes I had seen in the hands of my schoolmasters.

My mother took the cane in her hands, flexing it thoughtfully. The rattan made a soft, ominous hiss as she swished it through the air. She stood before me, her saree immaculate, her spectacles glinting in the fading light. “Suman,” she said, her voice calm but firm, “do you know what this is for?”

I nodded, my head bowed, cheeks burning with shame and dread. “Yes, Mother,” I whispered, my voice barely more than a breath.

“You were pleased when your school abandoned the cane,” she continued, “but see what has come of it. Your father and I have decided that discipline must be maintained at home. From now on, you will be punished for both academic and behavioural failings. I shall administer the cane when necessary.”

(pause) She paused, her eyes softening for a moment. “It will be a bitter medicine, but it is for your own good. We love you dearly, and we wish to see you grow into a fine, upright man. I will not hesitate to be strict, for your sake.”

My heart pounded as I imagined the sting of the cane. Never before had my mother so much as slapped my hand, and now, in my teens, I was to be caned like a naughty schoolboy. The thought filled me with dread, but also a strange resolve to do better. For in those days, every child knew that a spanking, though painful, was a lesson in itself—a lesson in obedience, humility, and the importance of striving for one’s best.

From that day forward, my mother became both tutor and disciplinarian. Each evening, she sat beside me at my desk, the cane resting within easy reach. Her lessons were thorough and patient, her expectations high. When I faltered—when my mind wandered or my answers were careless—she would remind me of the cane, her fingers tapping its length with quiet authority. The mere sight of it was enough to set me straight, but sometimes sterner measures were needed.

(short pause) There were times, of course, when I failed to meet her standards. On those occasions, she would instruct me to stand, and with a steady hand, she would administer a measured punishment. The cane would sing through the air and land with a sharp, stinging bite across the seat of my trousers. I would grit my teeth, determined not to cry, for every child knew that tears were best saved for true sorrow, not for the just consequences of one’s own failings. Afterwards, my mother would comfort me, her voice gentle and kind, reminding me that each stroke was given out of love and hope for my future.

The days passed in this way, each one marked by study, discipline, and the ever-present cane. Gradually, my work improved. My marks climbed higher, and my confidence grew. The cane, once a symbol of fear, became a reminder of my mother’s unwavering care and her belief in my potential. I learned that a spanking, when given with love and fairness, could be a stepping stone to greater things.

(pause) By the time my final exams arrived, I was ready. I sat each paper with a steady hand and a clear mind, the memory of the cane guiding me to do my best. When the results came, they were better than ever—marks above ninety-five percent in every subject, my class rank restored.

My mother’s eyes shone with pride as she read the results. Without a word, she took the cane, snapped it in two, and placed it in the rubbish bin. “You have learned well, Suman,” she said, her voice warm with affection. “Discipline and love go hand in hand. Remember this always, and you will never go astray.”

(long pause) And so, in the gentle twilight of my childhood, I learned that a firm hand, guided by love, could shape not only my behaviour, but my very character. The lessons of those days, and the sting of the cane, have stayed with me ever since—a bittersweet memory, and a moral to carry into the world. For every child, a little discipline, given with love, is the surest path to a bright and upright future.