(gap: 2s) In the gentle cradle of my childhood, the world was a patchwork of red-brick cottages, misty mornings, and the comforting scent of coal smoke drifting from chimneys. Our Kentish village, Little Wingham, bustled with the laughter of children in hand-me-down jumpers, their knees perpetually scuffed from games on the green. Mothers, wrapped in tweed coats and headscarves, gathered by the corner grocer, their voices weaving a tapestry of gossip and gentle admonishments. The air was always tinged with the earthy perfume of wild primroses and the distant promise of the sea.

(short pause) My own home was a modest cottage, its sitting room warmed by a coal fire and the ever-present aroma of strong tea. Faded floral curtains framed the windows, and crocheted blankets softened the battered armchairs. The kitchen was alive with the clatter of crockery and the gentle hum of my mother’s voice as she poured tea from her brown pot, her cardigan buttoned up tight against the morning chill. There was a sense of order and routine, a rhythm to the days that felt as old as the village itself.

(pause) My mother, in those days, was the very picture of 1950s practicality—a figure who could have stepped straight from the pages of a well-thumbed children’s book. She dressed with a simple, unpretentious grace: a sturdy wool skirt, always pressed and falling just below the knee, paired with a sensible blouse in soft pastels or faded florals. Over this she wore her favourite cardigan, buttoned all the way up, a brooch pinned neatly at the collar. Her shoes were stout and polished, made for walking the village lanes and standing for hours at the stove. On her head, a plain headscarf was tied firmly beneath her chin, keeping her hair—always brushed and pinned—tidy and out of the way. Her hands, though gentle, bore the faint marks of housework: a little red from scrubbing, nails kept short and clean. She moved with a brisk, no-nonsense efficiency, her back straight, her chin lifted, and her eyes sharp as a sparrow’s. There was a certain set to her jaw, a firmness in her step, that brooked no argument. When she entered a room, the air seemed to settle; her presence commanded respect, not through harshness, but through the quiet authority of someone who knew her mind and expected to be obeyed. She stood for no nonsense—her rules were clear, her expectations unwavering, and her love, though sometimes stern, was as steady as the ticking of the kitchen clock.

(pause) Yet, beneath this gentle surface, childhood was not without its shadows. In those days, the matter of discipline was as much a part of life as the changing seasons. At my primary school in France, the law was curiously silent on the matter of corporal punishment. It was neither forbidden nor encouraged, and so the decision was left to the teachers—some of whom wielded their authority with a heavy hand. I, alas, had the misfortune of encountering two such teachers during my ninth and tenth years, and their penchant for discipline left a lasting impression on my young heart.

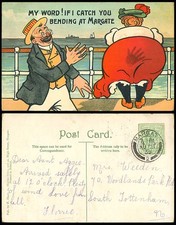

(short pause) There was a peculiar humiliation in being summoned to the front of the class, the eyes of my classmates prickling at my back. The teacher’s lap awaited, and I would have to settle myself across it, cheeks burning with shame. The sting of two dozen slaps, sharp and unyielding, would rain down, and though I tried to be brave, tears always came. The walk back to my desk was the worst of all—a march of shame, my face blotched and wet, my classmates’ eyes averted in silent sympathy or secret relief.

(pause) Most times, the ordeal ended there. The pain faded, and the lesson was learned, at least for a while. Only if the matter was grave would I be sent to the headmistress, where the punishment was more severe: trousers and underpants lowered, a formal note for my parents, and a bottom that smarted for days. But for a long while, I was spared the double indignity of punishment at home, for my mother believed she would be notified of every school spanking. This happy misunderstanding shielded me from many a sore backside.

(short pause) That is, until one fateful Saturday. The village was alive with the usual weekend bustle—mothers chatting by the red telephone box, children darting between the swings and the grocer’s door. After our morning lessons, I found myself embroiled in a childish squabble with a classmate, our voices rising above the hum of village life. I teased him about his clumsy football skills, crowing, “At least I know how to score a penalty kick!” He shot back, quick as a flash, “Well, at least I haven’t been smacked by Mrs Lavaux, like you have!”

(pause) The words hung in the air, sharp as a slap. I opened my mouth to retort, but my mother’s voice cut through the chatter, low and dangerous. “Oh yes?” she said, her eyes narrowing. “I’d be very interested to know when that happened.” She didn’t press my friend for details, but I felt a cold knot of dread settle in my stomach. I knew, with the certainty of a child who has lived through such moments before, that the matter was far from closed.

(short pause) The drive home was silent, the only sound the gentle rattle of the Morris Minor and the distant call of a blackbird. My mother’s lips were pressed into a thin line, her hands gripping the steering wheel. I sat beside her, my heart thumping, hoping against hope that she would forget my classmate’s careless words. But mothers, as I would learn, rarely forget such things.

(pause) As soon as we arrived, she sent me to my bedroom—a small, tidy space with twin iron beds, crocheted eiderdowns, and a much-loved stuffed rabbit perched on the pillow. The “Visit Kent!” poster on the wall seemed to mock my predicament. I sat on the edge of the bed, swinging my legs and listening to the muffled sounds of my mother moving about the house. The wait was agony, each minute stretching out like an eternity.

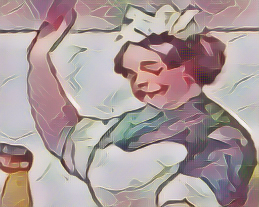

(short pause) At last, she entered, her slippers soft against the worn linoleum. She sat on my bed, her expression grave, and asked, “Why were you smacked at school, as your friend said?” My answer was slow, my voice trembling. “I… I was talking in class, Maman. I’m sorry.” But my apology was not enough. With practiced efficiency, she lowered my trousers and underpants, her hands cool and firm. I felt the familiar surge of shame and fear as she guided me over her lap, my face pressed into the eiderdown, the scent of lavender and old wool filling my nose.

(pause) Her palm was swift and sure, each smack echoing in the small room. The pain was sharp, but it was the scolding that stung most. “You must respect your teachers, Daniel. Your studies are important. I will not have you behaving like a hooligan.” Her words, spoken in that stern, loving voice, cut deeper than any slap. I wept, my tears soaking the blanket, my legs kicking helplessly.

(short pause) Suddenly, she paused. I dared to hope it was over, but she held me fast. “Daniel,” she said, her voice softer now, “why didn’t you tell me you had been punished?” I hesitated, then whispered the truth: “Because I knew you would smack me too.” For a moment, I thought she might relent, but instead her face grew even sterner.

(pause) “That was a very unwise choice, my boy,” she said, her words heavy with disappointment. “And I’m afraid it has only made things worse for you.” With that, she slipped off her right slipper—a sturdy thing with a well-worn sole—and picked it up. Before I could protest, the slipper descended, its sting far sharper than her hand. I howled, the pain blooming across my backside, my fists clenching the eiderdown. The sound of the slipper was a steady rhythm, punctuated by my sobs and her firm admonishments.

(short pause) She paused again, her breath coming a little faster. “Tell me, Daniel, has this happened before?” I could not answer, my silence betraying me. She sighed, then resumed the slippering, each smack a lesson in honesty and obedience. When at last she stopped, I lay limp across her lap, my tears spent, my bottom throbbing with heat. The slipper, when she rested it against my skin, was warm—almost hot—from its work.

(pause) She helped me up, her face softening just a little. “Now, young man, you will stay in your bedroom for the rest of the weekend. And tomorrow, I will spank you again at bedtime, for hiding your school troubles. If you are smacked in school again, I expect to be told—and you can expect the slipper every time, on your bare bottom. Do you understand?” I nodded, my eyes downcast, the lesson seared into my memory as surely as the pain in my backside.

(short pause) Sunday passed in a haze of boredom and regret. I sat at my desk, the hard chair a constant reminder of my punishment, working through my homework and reading old adventure stories. The sounds of the village drifted in through the window—the distant shouts of children, the clatter of a milk cart, the gentle chime of the church bell. I longed to be outside, but dared not disobey.

(pause) That night, after brushing my teeth, I returned to my room to find my mother waiting, her right sleeve rolled up, the slipper in her hand. There was no need for words. With tears already prickling my eyes, I bent over her knee, my heart heavy. She took my wrist, holding it gently but firmly, and delivered my second spanking of the weekend. The pain was sharp, but it was the sense of justice—of order restored—that lingered longest.

(short pause) From that day on, I never failed to tell my mother about my school punishments, no matter how much I dreaded the consequences. The risk of a second helping was enough to keep me honest. Looking back, I see now the lessons woven through those painful moments: the importance of truth, the value of respect, and the enduring love that lay beneath even the sternest discipline.

(pause) Childhood, in those days, was a tapestry of joys and sorrows, of laughter and tears, of lessons learned at the hands of those who loved us most. And though the sting of the slipper has long since faded, the memories remain—vivid, bittersweet, and cherished, like the scent of primroses on a misty Kentish morning.