(gap: 2s) In the early 1960s, our small northern English town was a world unto itself, nestled between rolling green hills and endless rows of red-brick terraces. The air was always tinged with the earthy scent of coal fires, and on Sunday mornings, the distant clang of church bells seemed to float above the rooftops, mingling with the laughter of children echoing down the cobbled streets. The sunlight would slant through the clouds, painting everything in a golden haze, and the world felt both boundless and safe—a place where adventure was never more than a few steps from your own front door.

The day before, all of us local kids had gathered in the woods just beyond the allotments, our hands sticky with sap and our knees stained green, determined to build the grandest den the north had ever seen. We scavenged planks, old tarpaulins, and bits of rope, our voices rising in excited debate over where the secret entrance should be. We didn’t quite finish, but as the sun dipped behind the trees, we parted with a solemn promise to meet again after chapel the next day and carry on with our secret hideout. The anticipation buzzed in my chest all night, and I could barely sleep for thinking of what we’d build together.

After chapel, I noticed my father didn’t turn down our street as usual, but kept driving past the familiar rows of terraced houses. The car’s engine hummed, and I pressed my nose to the window, watching the world blur by. I piped up, asking where we were going, and that’s when I learned we’d be stopping at the Co-op to look at wallpaper and carpet for the bedroom they were doing up. My heart sank. The thought of missing out on the den, of letting my friends down, gnawed at me.

(short pause) Ours was a working-class family, but by the standards of our background, we were very well to do. My parents had both worked hard—Dad at the mill, Mum at the shop—and it showed in the little comforts we enjoyed. We had a car, which was rare for our street, and our home was always warm, with new wallpaper and a proper carpet underfoot. There was a quiet pride in how they’d managed to give us more than they’d ever had themselves, and I always felt a sense of comfort and security that set us apart, just a little, from many of our neighbours. Our kitchen always smelled of baking bread and stewed tea, and the living room was a patchwork of hand-me-downs and new treasures, each one a testament to their hard work.

(short pause) Of the two, it was always Mum who laid down the law. She was the strict one, never afraid to use a smack to keep us in line if she thought it was needed. Her voice could cut through any nonsense, and her eyes missed nothing. Dad, on the other hand, was more live-and-let-live—easygoing, sometimes even a bit henpecked, happy to let things slide unless Mum insisted otherwise. If there was discipline to be handed out, you could be sure it would be Mum who delivered it, while Dad would stand by, perhaps with a sympathetic look, but rarely intervening. That was just the way things were in our house. I sometimes wondered if Dad ever wanted to step in, but he always seemed to trust Mum’s judgment, and I suppose, in his own way, he was right to.

I pleaded with Dad, explaining that I was needed back home to help finish the den, and couldn’t he just let me off at the corner? My voice trembled with desperation, and I could feel the sting of tears threatening. But he shook his head, saying that at ten years old, I was far too young to be left on my own, and I’d have to come along to the shop. I slumped back in my seat, the weight of disappointment pressing down on me.

When we got to the Co-op, the world seemed to shrink. The shop was cool and dim, the air thick with the scent of floor polish and new linoleum. I put on my best performance. I sulked, I whinged, I begged, trying to convince them I should be home with my mates. My voice echoed off the high ceiling, and I could feel the eyes of the other shoppers on me, their faces a mixture of amusement and annoyance. My parents tried to calm me, but I was having none of it. Eventually, I flopped onto the linoleum floor and howled, my cheeks hot with frustration and shame. That’s when my mum left the wallpaper samples, marched to the front, and whispered something to the lady at the till.

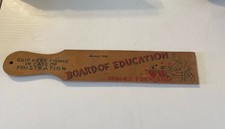

For a moment, I thought I’d won. Mum was telling the cashier she needed to get her little lad home to build his den. I watched her stride back towards me, heart leaping—until I saw the look on her face, and the wooden paint stirrer in her hand. My stomach dropped. The world seemed to slow, every sound growing sharper—the rustle of paper bags, the distant chime of the shop bell, the low murmur of voices. I knew that look: it was the one that meant there would be no more warnings, no more second chances. My heart pounded in my chest, and my mouth went dry.

Without a word, she took my hand and led me over to the carpet rolls. The roughness of her grip told me there would be no escape. Then, in her best Lancashire accent, she apologised to the whole shop for my behaviour and announced that her son needed a good telling-off. She said if anyone objected, they could look away or step outside. I was stunned—how had my victory turned so quickly to disaster? My face burned, and I wished I could disappear into the floor. The air felt thick and heavy, every eye in the shop suddenly on us, the silence broken only by the shuffling of feet.

Mum sat down on one of the big carpet rolls and stood me in front of her. The carpet’s scratchy texture pressed against my legs as she pulled me over her lap. I remember the sensation of her firm, steady hands guiding me, her grip unyielding but not cruel. She didn’t shout or scold—her discipline was always measured, almost ritualistic, as if she believed in the lesson as much as the punishment itself. I could feel the anticipation building, the dread of what was to come, and the humiliation of being so exposed in front of strangers. My cheeks burned with shame, and my eyes stung with unshed tears.

Then, with the paint stirrer in hand, she began. Each smack landed with a sharp, echoing crack, the sound bouncing off the high ceilings and tiled floors, louder than the church bells outside. The sting was immediate and real, a hot, prickling pain that seemed to radiate through my whole body. I tried to hold back the tears, but the combination of pain and embarrassment was overwhelming. I squeezed my eyes shut, willing myself to be brave, but the tears came anyway, hot and silent, rolling down my cheeks as I tried not to cry out. I could hear the faint murmurs of the other shoppers, a few claps from the older ladies—some approving, some perhaps just relieved it wasn’t their own child. That was the worst of it: the public nature of it all, the knowledge that my shame was on display for everyone to see.

Mum’s approach was never angry or out of control. She believed in discipline, but she also believed in fairness. She never hit harder than she thought was necessary, and she always made sure I understood why I was being punished. Even as the smacks landed, she spoke quietly, reminding me that my behaviour had consequences, that I was better than this, and that she loved me enough to teach me right from wrong. There was a strange comfort in her steadiness, even as I wished desperately for it all to be over.

When it was done, she set me gently on a stool by the wallpaper books. I sat there for what felt like an eternity, cheeks burning, as people glanced over, knowing exactly what had happened. The wallpaper patterns blurred before my eyes, and I tried to focus on the swirling flowers and stripes, anything to distract myself from the humiliation. My hands trembled in my lap, and I wished more than anything to be invisible. The pain in my skin faded quickly, but the sting of embarrassment lingered, a hot flush that wouldn’t go away.

(short pause) After a while, Mum came over and knelt beside me. She didn’t say much—just smoothed my hair, wiped away a stray tear, and told me quietly that it was over now. Her voice was gentle, and there was no trace of anger left, only a kind of tired understanding. She helped me to my feet, and together we finished the shopping, her hand resting reassuringly on my shoulder. I could feel the eyes of the other shoppers on us, but Mum held her head high, and I tried to do the same.