(gap: 2s) In the gentle days of my childhood, when the world seemed smaller and the sun shone kindly on the rows of pebble-dashed houses, I lived with my family on a modest estate in Surrey. Our home was not grand, but it was filled with the warmth of ordinary folk—mothers in housecoats, children in sturdy shoes, and fathers who worked hard and expected their children to do the same. The air was always tinged with the scent of cut grass and coal smoke, and the distant clatter of the milk float was our morning bell.

Each day began with the rattle of the letterbox and the cheerful whistle of the postman. My mother, ever brisk and bustling, would sweep into the kitchen in her housecoat, her hair set in curlers, and set about making tea. The kettle sang, and the aroma of PG Tips mingled with the faint tang of boiled eggs and soldiers. My father, tall and broad-shouldered, would read the Daily Mirror at the breakfast table, his brow furrowed as he pondered the news of the day.

My younger brother, three years my junior, was my constant companion and, at times, my shadow. He was a sprightly little fellow, with a mop of unruly hair and a gap-toothed grin that could charm even the sternest neighbour. Mother and Father, ever eager to show the neighbours that we were a proper family, insisted I look after him wherever we went. He was always trailing behind as we pedalled our battered Choppers along the lane, his legs pumping furiously to keep up. I would wait, watching my friends disappear ahead, a pang of longing in my chest. Sometimes, I felt a flicker of resentment, but I knew it was my duty as the elder, and I wore that responsibility like a badge.

Our estate was a world unto itself, a patchwork of privet hedges, cracked pavements, and the laughter of children echoing between the houses. The mums would gather by the corner shop, exchanging news and recipes, their voices rising above the hum of the milk float and the distant strains of a Beatles tune from a transistor radio. The jumble sale poster in the window promised treasures for a penny, and the Silver Cross prams lined up like sentinels outside the shop.

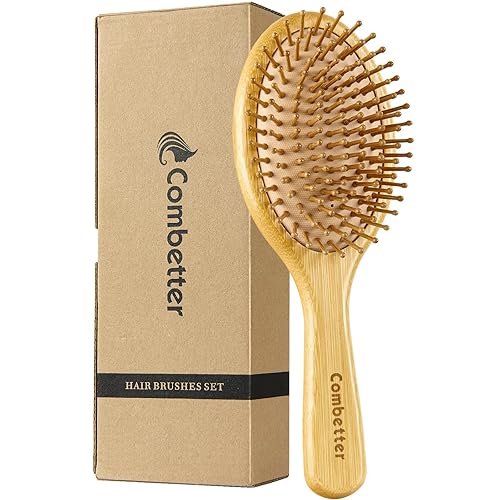

In our house, discipline was considered a virtue, and Mother believed in “character building.” We swept the garden path, weeded the flowerbeds, and polished the brass until it gleamed. The chores were many, but there was a certain pride in seeing the house shine. Sometimes, if I was especially careless, my bicycle would be taken away for a day or two, and I would watch it longingly from the window, vowing to do better. Spankings were rare, reserved for the gravest of misdeeds, and spoken of in hushed tones among the children of the estate. The mere mention of the wooden hairbrush on the sideboard was enough to make us all stand a little straighter.

One bright morning, as the sun peeked through the net curtains and the world seemed full of promise, news spread that the travelling fair had come to town. All the children were abuzz with excitement, their voices tumbling over one another as they made plans to cycle there together. The thought of bright lights, spinning rides, and the sweet taste of toffee apples set our hearts racing. But Father, with a grave look and a voice that brooked no argument, forbade us to ride our bicycles to the fair. “The road is too dangerous for your brother,” he said, and that was the end of it. My heart sank as I watched my friends set off, their mothers waving from the doorsteps, the sound of laughter fading into the distance.

Yet, fortune smiled upon us that day. A kindly neighbour, Mr. Jenkins, who always wore a tweed cap and smelled faintly of pipe tobacco, offered us a lift in his motorcar. We accepted with delight, bicycles and all, and I reasoned that we had not disobeyed Father’s command, for we had not cycled to the fair. The journey was a grand adventure in itself, the wind whipping through the open windows and the countryside rolling by in a blur of green and gold.

The fair was a wonderland of sights and sounds—bright lights twinkling against the evening sky, the cheerful music of the carousel, and the laughter of children mingling with the cries of the stallholders. My brother’s eyes grew wide as he won a goldfish in a plastic bag, and I felt a surge of pride as I guided him through the crowds. We shared a bag of toffee apples, our fingers sticky and our hearts full of joy. For a few precious hours, the world was a place of magic and possibility.

When the fair was over, Mr. Jenkins dropped us at our very door, and Mother and Father greeted him with smiles and thanks. My brother was fussed over, his goldfish admired, and for a moment, all seemed well. The sitting room glowed with the soft light of the electric fire, and the Bay City Rollers played quietly on the record player. But soon, Father’s face grew stern, and he led me to the sitting room, the curtains twitching across the street as neighbours watched with keen interest.

Mother joined us, her expression grave and her hands folded neatly in her lap. Father spoke first, his voice low and steady: “Mother, I shall leave this to you. See that he learns his lesson.” The words hung in the air, heavy as the scent of boiled cabbage from next door. I felt a chill run down my spine, for I knew at once that this was no ordinary punishment.

Mother took my hand and led me upstairs to my bedroom, her grip gentle but firm. Downstairs, my brother chattered about his goldfish, his laughter a distant echo. My bedroom, with its mismatched beds and threadbare Paddington Bear, felt suddenly small and cold. The “Visit Surrey!” poster curled at the edges, and the faded wallpaper seemed to close in around me.

She sat upon my bed, straightened her blouse, and beckoned me to her side. “You must learn to obey, my dear,” she said softly, “for obedience is the root of all good character.” Her voice was gentle, but her eyes were resolute. With that, she gently but firmly placed me across her knee, and I braced myself for what was to come.

I had never been spanked before, but I had heard the tales whispered among the children of the estate. Mother’s hand was steady as she delivered the first five smacks to one side, then five to the other. Each one stung, but I bit my lip and tried to be brave, for I knew that tears would only make it worse. The sound echoed in the small room, mingling with the distant strains of “Blue Peter” from the lounge.

There was a pause, and I dared to hope it was over. But Mother, believing in thoroughness, gave me ten more, slow and measured. The sting grew sharper, and my eyes filled with tears, though I tried not to let them fall. I thought of the stories my friends had told, and I wondered if they, too, had felt this mixture of shame and resolve.

Then, with a change of pace, she delivered ten quick, sharp smacks to the backs of my thighs. The pain was keen, and I could not help but cry out, burying my face in the bedspread. The room seemed to spin, and I clung to the familiar scent of lavender and old books, seeking comfort in the midst of my distress.

Mother waited a moment, her hand resting gently on my back, then returned to my backside, giving ten more, slow and deliberate. By now, I was sobbing quietly, my pride and my skin both smarting. The lesson was not yet complete, and I knew that Mother’s resolve was as strong as ever.

Another set of ten, spaced out and firm, made me cry aloud. I clutched the bedspread and begged forgiveness, promising never to disobey again. Mother’s face was kind, but her voice was unwavering. “You must learn, my dear. The world is not always gentle, and you must be strong.”

Mother finished with ten more to my thighs, swift and stinging. My legs kicked and twisted, but she held me gently, determined that I should learn. Two more rounds of slow, spaced-out smacks followed, and then a final flurry that left me breathless and spent. At last, Mother stood and allowed me to slide to the floor, my head resting on